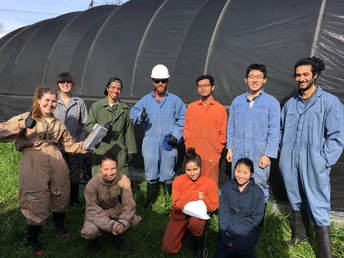

Spring 2017 Field Team Spring 2017 Field Team I didn’t expect to become a personnel manager in graduate school. Independent by nature, I pictured myself as a solo actor, laboring alone in the lab till odd hours producing results. Little did I know – I was very wrong about working solo! In the last 4+ years I’ve worked with over 50 undergraduate student interns on my research project. I am firmly a middle manager within the well-oiled academic hierarchy. Having priced themselves out of the fun (they might say tedium), our advisers are rarely in the lab and field. Instead they rely on us graduate students to manage our research projects and conduct the research tasks. As we work, we learn, and in turn eventually “price” ourselves out of the more routine tasks in research, like processing samples. I rely on interns to complete this work. In turn, these more accessible tasks are a valuable way for interns to gain practical research skills and engage with the research process beyond any experience they get in courses. Just like my adviser relies on me, I am completely reliant on my interns. They are essential member of our research team; there’s simply too much work for one person. Perhaps more importantly, I am sharing the research experience with future scientists. As an undergraduate, I conducted my senior thesis at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory through a research internship program. This was a profoundly formative experience for me, and I want to pass this type of experience on to other budding scientists. In selecting the highest quality applicants, I consistently end up with interns who are members of groups underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. A former woman of color mentee told me she found a safe place in our lab to explore science within the larger UC Berkeley campus. As a white, queer male, it meant a lot to me to hear that. On a day to day level, working with interns is a great experience for me. It gives structure to my research as I plan tasks and estimate time for completion. It’s also my responsibility to give them context for their work. In the midst of prepping hundreds of samples, it can be easy to forget that each sample becomes a data point that will be interpreted to prove or disprove our hypotheses. Once an experiment is designed and underway, the results are only as good as the samples. I recently had an intern who collected samples in the field and then, instead of delivering them to the lab fridge immediately afterwards as instructed, took them to class and then home with him. I let him go. I’ve had other funny instances too. I once had an intern who loved to sing, very loudly in Chinese, as he watered the plants at my field site. That field site is in a residential neighborhood, and I wonder how the neighbors felt about the entertainment. A wonderful intern who still works for me, usually in the lab, came out to the field site to sample one afternoon, and I learned she has a great dislike of frogs. Unfortunately for her, our field site greenhouse is inhabited by the Pacific Chorus Frog (see July blog post). She stated that she was able to get used to all the spiders in our other greenhouse, but drew the line at frogs and would be happier in the lab. My interns no doubt have had funny instances with me, too. They are very patient if I forget to send them something while out at a conference or in the field. Sometimes we work on such a tight schedule that the dishes pile up and I have them wash dishes for 4 hours – only to turn around and get them dirty again. Washing dishes in a lab is a crucial skill, so I don’t hesitate to ask interns to help out. Just like the quality of the results is limited by the quality of the samples, the quality of all work in the lab is limited by the cleanliness of the glassware. We prioritize washing and reusing materials like syringes and large pipette tips, as a part of our Green Labs Certification. This means we use water and labor in order to produce less solid waste and consume less plastic. Is this worth it? Along with asking a sustainability expert, ask the interns. Some of my interns have gone on to work in related environmental fields. Two former interns work at oil companies, and I like to think they bring the sustainability principles we practiced in our research to these extractive industries. I’ve had several pre-med students who felt lab experience, even in a soils lab, would strengthen their med school applications. (There’s more overlap than you might think – syringes, delicate tweezers, sterile environments.) We’re now starting an enhanced internship program, the Sustainable Soils Research Incubator, with a grant from the Berkeley Collegium to narrow the gap between teaching and research here at Berkeley. Judging from the high demand on the part of the students, these internship programs work as well for the interns as they do for me and my adviser. Thank you, interns! I couldn't do it without you!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarick Matzen completed his PhD in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management department at University of California, Berkeley in 2020. He is now a postdoc in the Soil, Water, and Climate Department at the University of Minnesota working on iron cycling in marine systems. Archives

July 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed