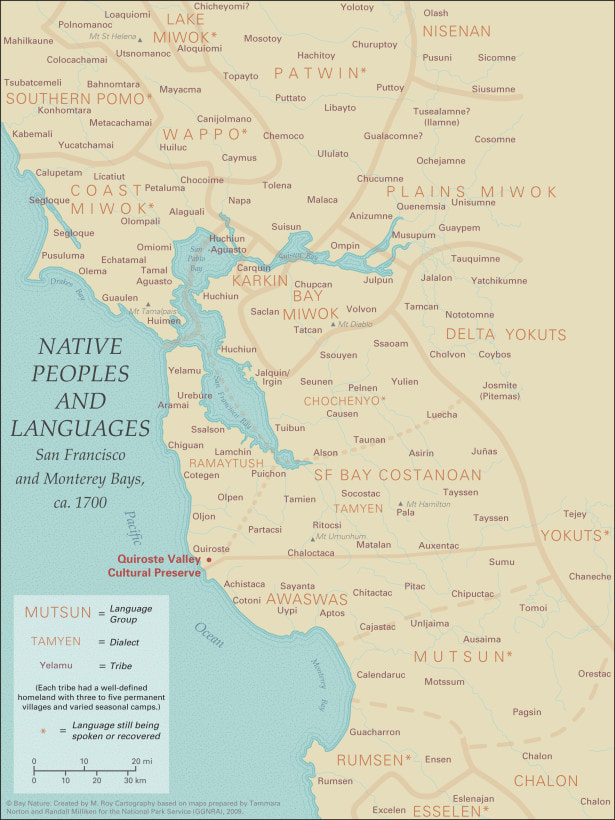

Competitive invasive Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica, to the left) crowds out native grasses (foreground, to right) at the Richmond Field Station. An old California Cap Company building connotes a settler dwelling. Competitive invasive Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica, to the left) crowds out native grasses (foreground, to right) at the Richmond Field Station. An old California Cap Company building connotes a settler dwelling. The bunchgrasses we were walking on could have been hundreds of years old. The “old growth at our feet,” these Danthonia californica plants and their neighboring species form the last remaining coastal terrace prairie on the San Francisco Bay Shore. It’s not farfetched to envision these same plants growing here before colonization. This 6 acre patch of prairie at UC Berkeley’s Richmond Field Station was undisturbed, despite being surrounded by chemical plants – acrylamide today to the west, to the east the former California Cap Company, with its legacy of mercury fulminate, and what was once Stauffer Chemical. I’m out there studying sustainable ways to clean up arsenic left in nearby soil as Stauffer chemical waste was dumped. Today we are walking around the undisturbed prairie talking about the last step of my restoration project, propagating prairie grasses from local germplasm to plant out in my field site. California native plant communities have never been far from my research. Research at my first field site, an old railroad grade in Berkeley slated to become a community orchard (but for the arsenic in the soil!) received funding from a large project that also supported the Amah Mutsun Tribe just south of here managing coastal grasslands. The Long Term Sustainability Through Place-based, Small-scale Economies project at Japan’s Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, headed by Junko Habu, a professor in the Anthropology Department here at UC Berkeley, wove together sustainability of societies ancient and modern, focusing on projects around the Pacific Rim. My project was firmly in the modern section, looking at sustainable methods to rehabilitate soils for urban food production, but our neighboring California projects worked with California Indigenous peoples, including the Amah Mutsun, to support traditional environmental resource management. Traditionally, coastal Indigenous people carefully tended the prairies and oak savannahs to increase important plant populations. As Kay Anderson describes in Tending the Wild, far from living a hardscrabble hunter-gatherer life, or living an ecological eunuch-like existence hardly impacting the earth, Indigenous people developed intimate relations with plants through generations of experimentation and observation. The coastal terrace prairie we see today thus reflects Indigenous cultures, not untouched wilderness. I was reminded of this recently when I saw Keshia Williams, a Berkeley Social Welfare lecturer, share her work to bring sustainability themes into a social welfare course. The presentation was a part of a year-long project I helped organize for Berkeley faculty to support them in bringing sustainability concepts into courses in diverse disciplines. Williams, a workshop participant, looked around her classroom to start her process, and saw who was there in the room to participate in the discussion. She saw that Native people were not there, a reflection of underrepresentation at UC Berkeley overall, where Native students make up only 1% of the student population, compared to 2% of the California population. In a calculated move, she used her grant money to pay two former students, Bonnie Lockhart, MSW and Makena Silva, MSW, both Native, to work with her to bring sustainability into her course. Lockhart and Silva centered their presentation on creating an altar in the classroom to hold space for the environment in the classroom, and simultaneously hold space for people in the environment. Items on the altar held spiritual, cultural, medicinal, and environmental significance, and the altar honored these connections that permeate the fabric of life. Plants deemed lesser in the Western conservation aesthetic, like the red and white willow used to make the baby basket on the altar, hold significance equal to grand oak trees. Back on the prairie, I felt excited about these connections as I collected seeds for Stipa pulchra (Purple Needle Grass), and also humbled, because these connections weren’t new. I thought about what I notice, and what I don’t, based on my awareness of my position as a white transman in a white supremacist culture. As my students and I figure out the best ways for us to propagate these plants, we touch on old knowledge, learned, practiced, and refined by generations of people who were then forcibly removed, killed, isolated, or assimilated, but certainly not erased. Survivors of genocide like the Amah Mutsun people today must still fulfill their obligation to the Creator, says Valentine Lopez, Amah Mutsun elder. Though they do not own land because they are not a federally recognized tribe, they access to land through the Amah Mutsun Land Trust where they use traditional ecological knowledge to restore grasslands. In a broader sense, our restoration project on the coastal terrace prairie, funded by a new Environmental Justice emphasis in Berkeley’s The Green Initiative Fund, also weaves together environmental and social sustainability. Our project supports students from underrepresented groups, myself included, in environmental science in gaining paid research, restoration, and leadership experience. Our project is short, though. Our final recommendation will be for UC Berkeley to partner with Ohlone people here in the East Bay to practice culturally appropriate restoration and decolonize this ancient prairie. Thanks to Keshia Williams for access to Tending the Wild and the Bay Nature article featuring Valentine Lopez.

1 Comment

|

AuthorSarick Matzen completed his PhD in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management department at University of California, Berkeley in 2020. He is now a postdoc in the Soil, Water, and Climate Department at the University of Minnesota working on iron cycling in marine systems. Archives

July 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed